Message queue vs message bus: the practical differences

6/29/2022 · 7 min read

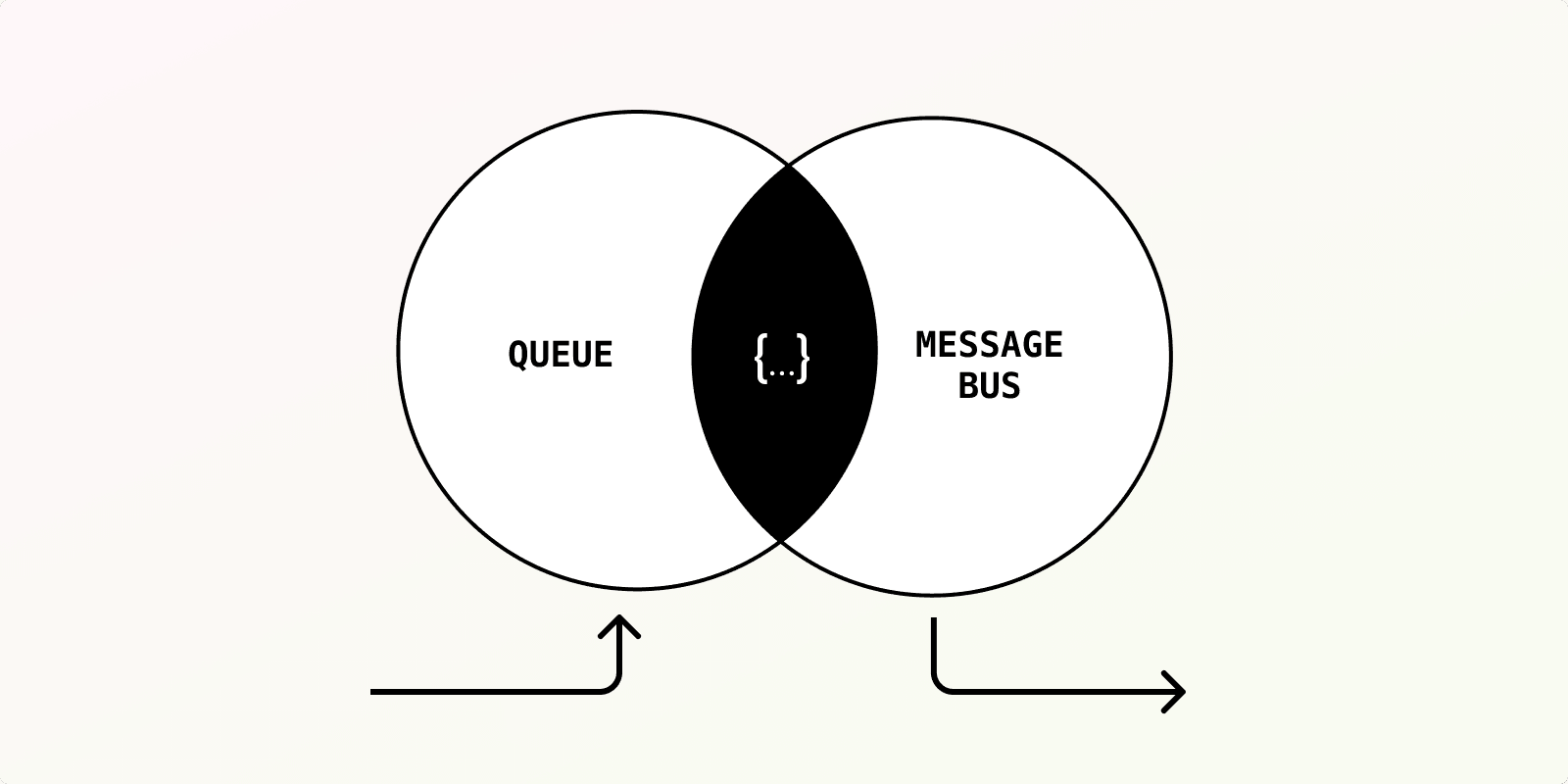

With modern implementations there’s a lot of overlap between message brokers and queueing systems. They’re similar: they share similar interfaces (sending and receiving events); they share many features; and they’re both used in complex products or at scale.

While similar, they’re (typically) used for different purposes. We thought we should break down the general distinction between the two and their general use cases, helping answer the question of ‘when should I use a queue vs a message bus’?

Quick note. Before we dive in, we should note that each type of message queue and message bus has their own implementation details, which affects the features and functionality. We’ll broadly generalize amongst the two categories here; there’s a ton to talk about in each of them!

So, apart from having a similar API in which:

- You push a message into the system

- Which is buffered and received by other services

How do queues differ from message brokers? Let’s talk about queues first.

A typical queueing system

A typical queue receives events, buffers them (typically persistently), and allows a worker to read from the queue to process the events. It gives you:

Ordering

Broadly speaking, queues give you an ordered series of events. They can be:

- FIFO (first-in-first-out), which means events are processed in the order that they’re re received.

- Ordered by time, which allows you to delay a message for a specific amount of time. This is particularly useful for scheduling jobs in advance.

It turns out that ordering by time is the biggest differentiator in modern queueing systems.

Message brokers — such as pub/sub, Kafka, Kinesis, etc. — typically deliver streams of events in (soft) real time without letting you schedule messages for the future.

You’d reach for a queueing system any time that you wanted to run delayed jobs in the background, and you’d need a queue to do this even if you had a message broker in your architecture already.

Coupling

It’s also typical that messages in a queue are consumed by a single worker: messages and workers are 1-1.

When you enqueue a message in eg. Celery or SQS, the message is intended to be received and processed by a single service that reads from the queue, once. This means that you typically have as many individual queues as you do individual workers: if you want to run more than one type of job, you’ll typically make another queue.

This doesn’t mean that things are single threaded: you can run workers in parallel, and most queues will ensure that a single message is claimed by one single process of the same worker.

Pull-based

It’s typical (but not always the case) that queues are pull-based. You’ll need to set up a subscription to your queue which reads and pulls new messages when available. This is usually handled by the queue’s SDK.

Retries

Most queueing implementations will handle retries for you, ensuring that the worker which processes your message is successful. If there’s an error, queues typically re-enqueue your message with exponential backoff and jitter.

Note that this is becoming more and more common within message brokers which support at least once delivery — which we’ll talk about soon.

Message queues are typically tied to distributed jobs which need to run in order or at specific times. They’re useful for business critical jobs which can be separated outside of your core services for availability, latency, and scale.

Most applications need a queue, whether it’s for something as basic as sending emails on signup (or communicating with your mail provider), or part of your application like publishing something at a specific time. It’s good practice to make sure your APIs handle the critical path only, pushing out other work to a queue.

A typical message bus

A message bus (or, message broker, event bus, or event broker) also accepts events to be received by other services, though they’re different than queues. Within a message broker, you typically send events to a ‘topic’ (instead of a queue) which is then received by one or more services — unlike a single service within a queue. It gives you:

Fan out

Most message brokers allow more than one service to subscribe to a topic. This allows you to have many systems react to a single event, and reduces coupling from your event to your workers.

Delivery guarantees

This one is hard to generalize. Your messaging systems can offer one of three delivery guarantees:

- At most once. These systems are almost always push-based; the message is pushed to subscribers, and you’ll receive it at most once. Retries aren’t handled here.

- At least once. These systems allow you to acknowledge that a message was received and processed. These are (typically) pull based; you’ll use an SDK within your services to subscribe and pull messages from the topic.

- Exactly once. This is essentially at least once with some idempotency built-in. It ensures that a message is processed exactly once by delivering messages more than once and preventing duplicates from being handled.

The delivery guarantees also imply the functionality you get from your queue.

Real-time distribution

In these systems, messages are sent as soon as they’re received. There’s no room to specify that messages should be delayed until some point in the future.

Scale

Message brokers are built for scale, often being able to handle billions of messages per day. It’s not required that each message invokes a specific function — it can be used to push events into storage, for example, for data analysis.

Message brokers often have other features, such as distributed request-reply across topics. They’re a central nervous system for events and coordination across distributed architectures. Typically, they aggregate events as things happen in your system, then allow you to build distributed services that hook into these events.

You’ll end up using these when you need scale and separate your items into microservices or an SOA — if that’s your thing.

High-level summary

Brokers and queues have similar interfaces — you send and receive messages within different parts of your app. That said, the delivery guarantees, scheduling, and coupling are large differences between both systems:

- Queues are typically 1:1, vs 1:N in message busses.

- Message busses typically are real-time, vs supporting scheduled messages (eg. for delayed jobs and future work)

- The implementation of event streams within a message bus is often different to queues. While both can share persistence, they’re designed for slightly different scale and use cases.

It’s typical that you’re going to need both a queue and a message broker when your system grows to some complexity.

Combining both together

At Inngest, we’ve mixed both message brokers and queues together to make it simple to write delayed jobs, background jobs, and asynchronous functions. It gives you the best of both:

You send events to us via HTTP. These are received by a broker, which processes the event. We then schedule step functions to run via a queue — either immediately or at some point in the future, if you’ve specified a delay.

If you’re interested, read out our docs on how to get started!